Interviews

Dieter Klein travels the world in the quest for the perfect photograph of abandoned cars

by James Mills

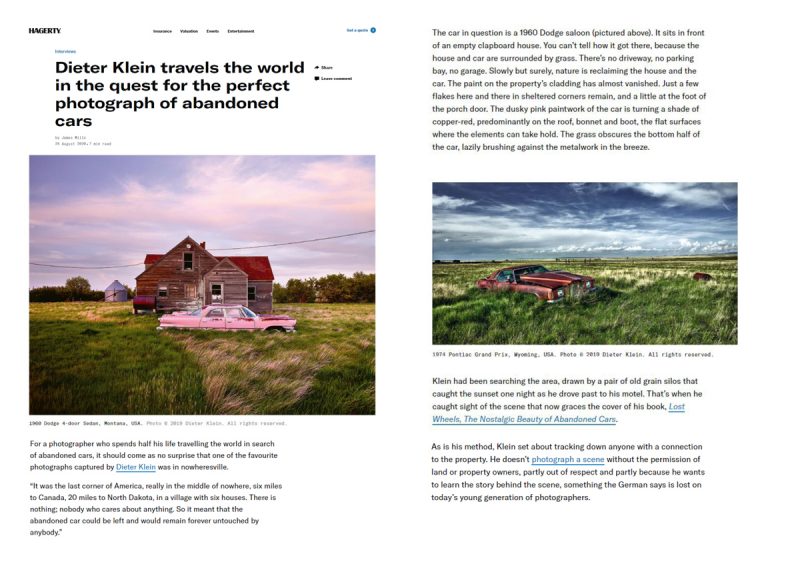

For a photographer who spends half his life travelling the world in search of abandoned cars, it should come as no surprise that one of the favourite photographs captured by Dieter Klein was in nowheresville.

“It was the last corner of America, really in the middle of nowhere, six miles to Canada, 20 miles to North Dakota, in a village with six houses. There is nothing; nobody who cares about anything. So it meant that the abandoned car could be left and would remain forever untouched by anybody.”

The car in question is a 1960 Dodge saloon (pictured above). It sits in front of an empty clapboard house. You can’t tell how it got there, because the house and car are surrounded by grass. There’s no driveway, no parking bay, no garage. Slowly but surely, nature is reclaiming the house and the car. The paint on the property’s cladding has almost vanished. Just a few flakes here and there in sheltered corners remain, and a little at the foot of the porch door. The dusky pink paintwork of the car is turning a shade of copper-red, predominantly on the roof, bonnet and boot, the flat surfaces where the elements can take hold. The grass obscures the bottom half of the car, lazily brushing against the metalwork in the breeze.

Klein had been searching the area, drawn by a pair of old grain silos that caught the sunset one night as he drove past to his motel. That’s when he caught sight of the scene that now graces the cover of his book, Lost Wheels, The Nostalgic Beauty of Abandoned Cars.

As is his method, Klein set about tracking down anyone with a connection to the property. He doesn’t photograph a scene without the permission of land or property owners, partly out of respect and partly because he wants to learn the story behind the scene, something the German says is lost on today’s young generation of photographers.

“At exhibitions, they just want to know, ‘Did you make the image on Photoshop?’ and when I explain it’s a real photograph, their next question is, ‘Where is the car?’ so they can go and photograph it. “So I tell them, ‘I travelled 44,000 miles in total. So I can tell you where this one scene is, but you will have to fly for perhaps 12 hours, drive maybe 2000 miles, and perhaps it’s still there or perhaps it’s been cleaned up,’ and normally it’s the end of the discussion.”

For his book, Klein estimates he spent 240 days travelling and on location, which accounts for around 10 per cent of the time he devoted to it. “The other 90 per cent is research.”

So there he is, in the middle of nowheresville, near the US-Canada border, knocking on the handful of doors in the area, when he meets Dale. Dale’s father had parked the Dodge in front of his house two days before he died. That was in 1977. Dale, now over seventy himself, had no use of the car or the house, and chose to leave the scene undisturbed – a memorial if you will – out of respect to his father.

“It is really fascinating,” says Klein, “so emotional; why should they store this car?” It wouldn’t happen, I venture, in European countries such as Klein’s home nation of Germany, or in Britain; the local council wouldn’t allow a property and car like the setting in Montana to stand derelict and open to passers-by. “Yes, officials would come directly and clean it up.”

Where it started

Now 63, Klein has been a professional photographer for more than forty years. As a teenager, he dreamed of becoming either a piano player, a graphic designer or a photographer. He says by the age of 17 he knew he wasn’t good enough to become a piano player, and his drawing and illustration skills weren’t up to scratch to see him through a career in the design industry. So he turned to photography, working for regional and national newspapers, and later specialist trade publications. But he says that all the way through that period, he searched for themes in his work, whether capturing industrial scenes or recording interviews with artists.

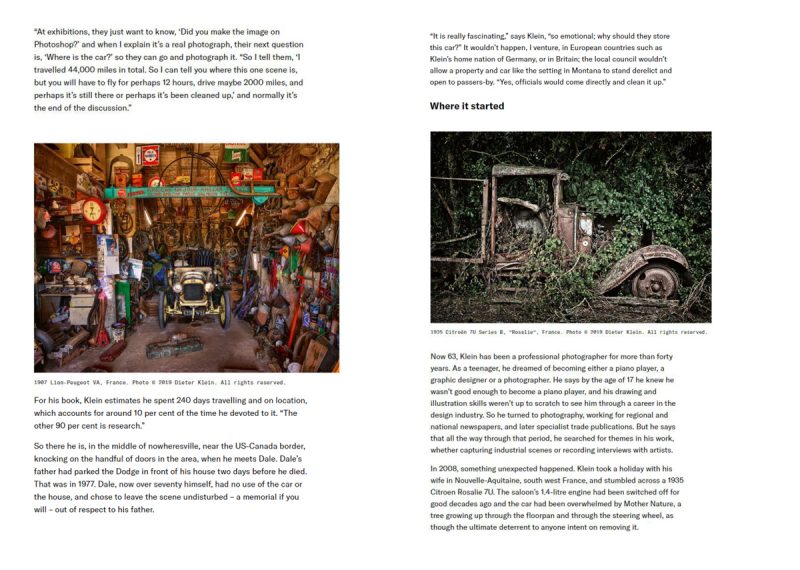

In 2008, something unexpected happened. Klein took a holiday with his wife in Nouvelle-Aquitaine, south west France, and stumbled across a 1935 Citroen Rosalie 7U. The saloon’s 1.4-litre engine had been switched off for good decades ago and the car had been overwhelmed by Mother Nature, a tree growing up through the floorpan and through the steering wheel, as though the ultimate deterrent to anyone intent on removing it.

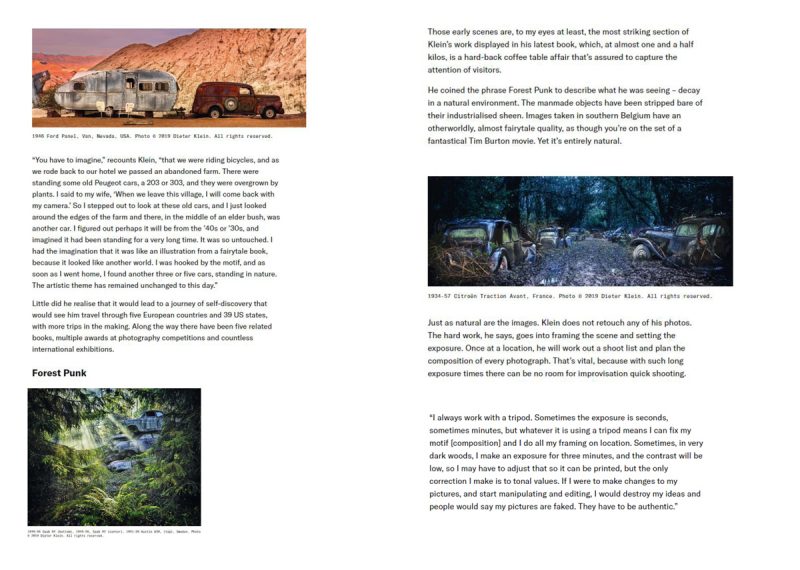

“You have to imagine,” recounts Klein, “that we were riding bicycles, and as we rode back to our hotel we passed an abandoned farm. There were standing some old Peugeot cars, a 203 or 303, and they were overgrown by plants. I said to my wife, ‘When we leave this village, I will come back with my camera.’ So I stepped out to look at these old cars, and I just looked around the edges of the farm and there, in the middle of an elder bush, was another car. I figured out perhaps it will be from the ’40s or ’30s, and imagined it had been standing for a very long time. It was so untouched. I had the imagination that it was like an illustration from a fairytale book, because it looked like another world. I was hooked by the motif, and as soon as I went home, I found another three or five cars, standing in nature. The artistic theme has remained unchanged to this day.”

Little did he realise that it would lead to a journey of self-discovery that would see him travel through five European countries and 39 US states, with more trips in the making. Along the way there have been five related books, multiple awards at photography competitions and countless international exhibitions.

Forest Punk

Those early scenes are, to my eyes at least, the most striking section of Klein’s work displayed in his latest book, which, at almost one and a half kilos, is a hard-back coffee table affair that’s assured to capture the attention of visitors.

He coined the phrase Forest Punk to describe what he was seeing – decay in a natural environment. The manmade objects have been stripped bare of their industrialised sheen. Images taken in southern Belgium have an otherworldly, almost fairytale quality, as though you’re on the set of a fantastical Tim Burton movie. Yet it’s entirely natural.

Just as natural are the images. Klein does not retouch any of his photos. The hard work, he says, goes into framing the scene and setting the exposure. Once at a location, he will work out a shoot list and plan the composition of every photograph. That’s vital, because with such long exposure times there can be no room for improvisation quick shooting.

“I always work with a tripod. Sometimes the exposure is seconds, sometimes minutes, but whatever it is using a tripod means I can fix my motif [composition] and I do all my framing on location. Sometimes, in very dark woods, I make an exposure for three minutes, and the contrast will be low, so I may have to adjust that so it can be printed, but the only correction I make is to tonal values. If I were to make changes to my pictures, and start manipulating and editing, I would destroy my ideas and people would say my pictures are faked. They have to be authentic.”

He works with digital equipment – “I was one of the first to change, because I was very fascinated that you get your result in two seconds” – with medium format cameras capable of producing a 100 megapixel image. “It’s not necessary for a book like this. But the size of the images, the tonal values and the contrast of these big backs is fantastic,” enthuses Klein.

For those amateur photographers interested, Klein only uses Phase One cameras. He switched to the Danish brand early on in his endeavours recording abandoned vehicles, after spending 25 years using Hasselblad equipment before experiencing a problem in the field and getting no help “or even an acknowledgement” from the Swedish camera manufacturer.

When Klein started out, the internet was of no use. All his detective work was done the old fashioned way, asking friends, consulting photographers, scouting locations, writing letters and knocking on doors. But over time, as the technology has leant a hand, he has seen locations laid to waste – in one instance after details were leaked out by others with looser lips than Klein, resulting in regional television stations declaring sites a health hazard and alerting authorities to the location.

The people behind the photos

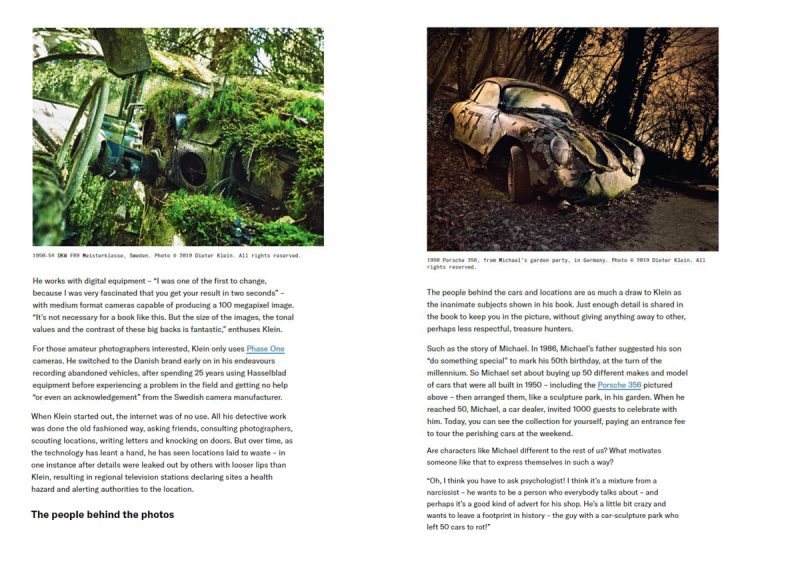

The people behind the cars and locations are as much a draw to Klein as the inanimate subjects shown in his book. Just enough detail is shared in the book to keep you in the picture, without giving anything away to other, perhaps less respectful, treasure hunters.

Such as the story of Michael. In 1986, Michael’s father suggested his son “do something special” to mark his 50th birthday, at the turn of the millennium. So Michael set about buying up 50 different makes and model of cars that were all built in 1950 – including the Porsche 356 pictured above – then arranged them, like a sculpture park, in his garden. When he reached 50, Michael, a car dealer, invited 1000 guests to celebrate with him. Today, you can see the collection for yourself, paying an entrance fee to tour the perishing cars at the weekend.

Are characters like Michael different to the rest of us? What motivates someone like that to express themselves in such a way?

“Oh, I think you have to ask psychologist! I think it’s a mixture from a narcissist – he wants to be a person who everybody talks about – and perhaps it’s a good kind of advert for his shop. He’s a little bit crazy and wants to leave a footprint in history – the guy with a car-sculpture park who left 50 cars to rot!”

He laments the position photography finds itself in today, where so little value is placed in the artform – “you have website selling photographs for one pound or two Euros now” – and divides his time between commercial work and his Abandoned Cars project.

Those poring over the index of his book in the hope of planning location visits of their own may be disappointed. Klein assures me that where someone asks for him not to reveal a location, he keeps it a secret.

We return to the cover image of Lost Wheels. Why that photograph, I ask? “For me, it expresses everything inside that I wanted to show. It’s contradictory, it’s calm, it’s peaceful, and it’s a kind of photography style. So for me this is a big shot.”

Rest assured, if you treat yourself to a copy of the book, you will be able to savour several hundred pages of big shots.

Dieter Klein reist um die Welt auf der Suche nach dem perfekten Foto von verlassenen Autos

von James Mills

Für einen Fotografen, der sein halbes Leben damit verbringt, die Welt auf der Suche nach verlassenen Autos zu bereisen, sollte es keine Überraschung sein, dass eines der Lieblingsfotos von Dieter Klein in Nirgendwo in Nirgendwo-Ville aufgenommen wurde.

„Es war die letzte Ecke Amerikas, wirklich mitten im Nirgendwo, sechs Meilen nach Kanada, 20 Meilen nach North Dakota, in einem Dorf mit sechs Häusern. Es gibt nichts; niemanden, der sich um etwas kümmert. Es bedeutete also, dass das verlassene Auto zurückgelassen werden konnte und für immer von niemandem mehr berührt werden würde.“

Bei dem fraglichen Auto handelt es sich um eine Dodge-Limousine von 1960. Sie steht vor einem leeren Schindelhaus. Man kann nicht sagen, wie es dorthin gekommen ist, da das Haus und das Auto von Gras umgeben sind. Es gibt keine Einfahrt, keinen Parkplatz und keine Garage. Langsam aber sicher erobert sich die Natur das Haus und das Auto zurück. Die Farbe auf der Verkleidung des Hauses ist fast verschwunden. Nur noch ein paar Spuren hier und da in geschützten Ecken, und ein wenig am Fuß der Verandatür. Die dunkle rosa Lackierung des Autos nimmt einen kupferroten Farbton an, vor allem auf dem Dach, der Motorhaube und dem Kofferraum, den flachen Flächen, wo die Elemente Halt finden können. Das Gras verdunkelt die untere Hälfte des Wagens und streift bei einer Brise gegen das Metall.

Klein hatte die Gegend abgesucht, angezogen von einem Paar alter Getreidesilos, die eines Abends den Sonnenuntergang einfingen, als er an seinem Motel vorbeifuhr. Da erblickte er die Szene, die jetzt den Einband seines Buches „Lost Wheels, The Nostalgic Beauty of Abandoned Cars“ ziert.

Wie es seine Vorgehensweise ist, machte sich Klein daran, jemanden aufzuspüren, der eine Verbindung zu dem Anwesen hat. Er fotografiert keine Szene ohne Erlaubnis von Land- oder Grundstückseigentümern, teils aus Respekt und teils, weil er die Geschichte hinter der Szene kennen lernen will, etwas, von dem der Deutsche sagt, dass es bei der heutigen jungen Generation von Fotografen verloren geht.

„Bei Ausstellungen wollen sie nur wissen: ´Hast du das Bild mit Photoshop gemacht?`, und wenn ich erkläre, dass es ein echtes Foto ist, lautet die nächste Frage: ´Wo ist das Auto?` Also sage ich ihnen: ´Ich bin insgesamt 44.000 Meilen gereist. Also kann ich Ihnen sagen, wo diese eine Szene ist, aber Sie müssen vielleicht 12 Stunden fliegen, vielleicht 2000 Meilen fahren, und vielleicht ist es noch da oder vielleicht wurde es abgeräumt`, und normalerweise ist das das Ende der Diskussion.“

Für sein Buch schätzt Klein, dass er 240 Tage auf Reisen und vor Ort verbrachte, was etwa 10 Prozent der Zeit ausmacht, die er dafür aufgewendet hat. „Die anderen 90 Prozent sind Recherchearbeiten.“

Da ist er also mitten in Nirgendwo in der Nähe der Grenze zwischen den USA und Kanada und klopft an eine Handvoll Türen in der Gegend bis er Dale trifft. Dales Vater hatte den Dodge zwei Tage bevor er starb vor seinem Haus geparkt. Das war 1977. Dale, der inzwischen selbst über siebzig Jahre alt, hatte weder das Auto noch das Haus danach genutzt und entschied sich aus Respekt seinem Vater gegenüber, den Schauplatz unverändert zu belassen – eine Gedenkstätte, wenn Sie so wollen.

„Es ist wirklich faszinierend“, sagt Klein, „so emotional; warum sollten sie dieses Auto aufbewahren?“ In europäischen Ländern wie Kleins Heimatland Deutschland oder in Grossbritannien würde das, so wage ich zu behaupten, nicht passieren; der Gemeinderat würde es nicht zulassen, dass ein Grundstück und ein Auto wie die Szenerie in Montana baufällig und für Passanten offen stehen. „Ja, Beamte würden direkt kommen und es aufräumen lassen.“

Wo es begann

Der heute 63-jährige Klein ist seit mehr als vierzig Jahren professioneller Fotograf. Als Teenager träumte er davon, entweder Pianist, Grafikdesigner oder Fotograf zu werden. Im Alter von 17 Jahren, sagt er, wusste er, dass er nicht gut genug war, um Pianist zu werden, und seine Zeichen- und Illustrationsfähigkeiten reichten nicht aus, um eine Karriere in der Designbranche zu durchlaufen. Also wandte er sich der Fotografie zu und arbeitete für regionale und überregionale Zeitungen und später für Fachzeitschriften. Aber er sagt, dass er während dieser ganzen Zeit nach Themen in seiner Arbeit suchte, ob er nun Industrieszenen festhielt oder Interviews mit Künstlern aufnahm.

Im Jahr 2008 geschah etwas Unerwartetes. Klein machte mit seiner Frau Urlaub in der Nouvelle-Aquitaine im Südwesten Frankreichs und stieß dabei auf einen Citroen Rosalie 7U von 1935. Der 1,4-Liter-Motor der Limousine war schon vor Jahrzehnten abgeschaltet worden, und das Auto war von Mutter Natur übernommen worden, von einem Baum, der durch die Bodenplatte und durch das Lenkrad wuchs, als wäre dies die ultimative Abschreckung für jeden, der ihn entfernen wollte.

„Man muss sich vorstellen“, erzählt Klein, „dass wir Fahrrad fuhren, und als wir zu unserem Hotel zurückfuhren, kamen wir an einem verlassenen Bauernhof vorbei. Dort standen einige alte Peugeot-Autos, ein 203 oder 303, und sie waren von Pflanzen überwuchert. Ich sagte zu meiner Frau: ´Wenn wir dieses Dorf verlassen, werde ich mit meiner Kamera zurückkommen. Also ging ich hinaus, um mir diese alten Autos anzuschauen`, und ich schaute nur um den Rand des Hofes herum, und da stand mitten in einem Holunderbusch ein weiteres Auto. Ich stellte mir vor, dass es vielleicht aus den 40er oder 30er Jahren stammt, und dass es schon sehr lange dort gestanden hatte. Es wirkte so unberührt. Es wirkte wie eine Illustration aus einem Märchenbuch, weil es wie aus einer anderen Welt aussah. Ich war ´süchtig` nach diesem Motiv, und sobald ich zu Hause war, fand ich drei oder fünf weitere Autos, die in der Natur standen. Dieses künstlerische Thema verfolge ich unverändert bis heute“.

Er ahnte kaum, dass es zu einer Reise der Selbstfindung führen würde, die ihn durch fünf europäische Länder und 39 US-Bundesstaaten führen würde, wobei weitere Reisen anstehen. Auf dem Weg dorthin gab es weitere Bücher, mehrere Auszeichnungen bei Fotowettbewerben und unzählige internationale Ausstellungen.

Forest-Punk

Diese frühen Szenen sind, zumindest in meinen Augen, der auffälligste Ausschnitt aus Kleins Werk in seinem neuesten Buch, das mit fast anderthalb Kilo ein Hardcover-Coffeetable Buch ist, das die Aufmerksamkeit der Besucher auf sich ziehen dürfte.

Er prägte den Ausdruck „Forest Punk“, um das zu beschreiben, was er sah – den Verfall in einer natürlichen Umgebung. Die von Menschenhand geschaffenen Objekte wurden ihres industrialisierten Glanzes beraubt. Bilder, die in Südbelgien aufgenommen wurden, haben eine überirdische, fast märchenhafte Qualität, so als befände man sich am Set eines fantastischen Tim-Burton-Films. Und doch ist es ganz natürlich.

Genauso natürlich sind die Bilder. Klein retuschiert keines seiner Fotos. Die harte Arbeit, sagt er, besteht darin, die Szene auszuwählen und die Belichtung einzustellen. An einem Drehort angekommen, plant er eine Aufnahmeliste und entscheidet die Komposition jedes einzelnen Fotos. Das ist unerlässlich, denn bei so langen Belichtungszeiten kann es keinen Raum für Improvisation und schnelle Aufnahmen geben.

„Ich arbeite immer mit dem Stativ. Manchmal beträgt die Belichtung Sekunden, manchmal Minuten, aber was auch immer es ist, mit einem Stativ kann ich mein Motiv [Komposition] bestimmen, und ich mache so meinen Bildausschnitt bereits vor Ort. Manchmal, in sehr dunklen Wäldern, mache ich eine Belichtung von drei Minuten, und der Kontrast wird niedrig sein, so dass ich das eventuell anpassen muss, damit es gedruckt werden kann, aber die einzige Korrektur, die ich vornehme, sind die von Tonwerten. Wenn ich Änderungen an meinen Bildern vornehmen und mit der Manipulation und Bearbeitung beginnen würde, würde ich meine Ideen zerstören, und die Leute würden sagen, meine Bilder seien gefälscht. Sie müssen authentisch sein“.

Er arbeitet mit einer digitalen Ausrüstung – „Ich war einer der ersten, der auf digitale Fotografie veränderte, denn ich war sehr fasziniert, dass man sein Ergebnis in zwei Sekunden erhält“ – mit Mittelformatkameras, die ein Bild mit 100 Megapixeln erzeugen können. „Für ein Buch wie dieses ist das nicht notwendig. Aber die Größe der Bilder, die Tonwerte und der Kontrast dieser großen Rückwände sind fantastisch“, schwärmt Klein.

Für interessierte Amateurfotografen: Klein verwendet nur PhaseOne-Kameras. Er wechselte schon früh zu der dänischen Marke, nachdem er 25 Jahre lang mit Hasselblad-Ausrüstung gearbeitet hatte, bevor er vor Ort ein Problem hatte und vom schwedischen Kamerahersteller keine Hilfe „oder auch nur eine Hinweis“ erhielt.

Als Klein anfing, war für ihn das Internet noch nutzlos. Seine gesamte Detektivarbeit wurde auf die altmodische Art und Weise erledigt: er fragte Freunde, konsultierte Fotografen, kundschaftete Standorte aus, schrieb Briefe und klopfte an Türen. Doch im Laufe der Zeit, als mit dieser Technologie vieles veröffentlicht wurde, hat er gesehen, wie Standorte verwüstet wurden – in einem Fall, nachdem Details von anderen mit lockereren Lippen als Klein durchgesickert waren, was dazu führte, dass regionale Fernsehsender Standorte als gesundheitsgefährdend deklarierten und die Behörden auf den Standort aufmerksam machten.

Die Menschen hinter den Fotos

Die Menschen hinter den Autos und Orten ziehen Klein ebenso an wie die unbelebten Subjekte, die in seinem Buch gezeigt werden. Das Buch enthält gerade so viele Details, dass Sie immer im Bilde sind, ohne anderen, vielleicht weniger respektvollen Schatzsuchern, etwas zu verraten.

Wie zum Beispiel die Geschichte von Michael. 1986 schlug Michaels Vater seinem Sohn anlässlich seines 50. Geburtstages zur Jahrtausendwende vor, „etwas Besonderes zu tun“. Michael machte sich also daran, 50 verschiedene Marken und Modelle von Autos zu kaufen, die alle 1950 gebaut worden waren – einschließlich des oben abgebildeten Porsche 356 – und sie dann als Skulpturenpark in seinem Garten zu arrangieren. Als er 50 Jahre alt wurde, lud Michael, ein Autohändler, 1000 Gäste ein, um mit ihm zu feiern. Heute können Sie sich selbst ein Bild von der Sammlung machen und zahlen einen Eintrittspreis, um am Wochenende eine Führung durch die untergegangenen Autos zu machen.

Sind Charaktere wie Michael anders als der Rest von uns? Was motiviert jemanden wie ihn, sich auf diese Weise auszudrücken?

„Oh, ich glaube, das müssen Sie einen Psychologen fragen! Ich glaube, es ist eine Mischung aus einem Narzissten – er will ein Mensch sein, über den alle reden – und vielleicht ist es eine gute Art Werbung für sein Geschäft. Er ist ein bisschen verrückt und will einen Fussabdruck in der Geschichte hinterlassen – der Typ mit einem Auto-Skulpturenpark, der 50 Autos verrotten liess!“

Klein beklagt die Position, in der sich die Fotografie heute befindet, wo der Kunstform so wenig Wert beigemessen wird – „man hat jetzt eine Website, auf der man Fotografien für ein Pfund oder zwei Euro verkaufen kann“ – und teilt seine Zeit zwischen kommerzieller Arbeit und seinem Projekt Abandoned Cars auf.

Diejenigen, die über den Index seines Buches brüten in der Hoffnung, eigene Ortsbesichtigungen zu planen, könnten enttäuscht sein. Klein versichert mir, dass er, wenn ihn jemand bittet, einen Ort nicht preiszugeben, er ihn geheim hält.

Wir kehren zum Titelbild von Lost Wheels zurück. Warum dieses Foto, frage ich? „Für mich drückt es alles aus, was ich damit zeigen wollte. Es ist widersprüchlich, es ist ruhig, es ist friedlich, und es ist eine Art von Fotostil. Für mich ist das also eine große Aufnahme.“

Seien Sie versichert, wenn Sie sich ein Exemplar des Buches gönnen, können Sie mehrere hundert Seiten grossartige Aufnahmen geniessen.